Periodic catatonia

Update : June 2016

Periodic catatonia, as defined by the WKL school, is not the simple recurrence of DSM/CIM defined catatonic episodes. The WKL concept is also very different from the clinical picture of "periodic catatonia" described by Gjessing. Unfortunately this homonyms is responsible for a systematic confusion between the two in the literature.

For the WKL school, periodic catatonia is a non-systematised schizophrenia. "Non-systematized" means that it is not restricted to a single neurological system, and "schizophrenia" that the disorder comes with residual symptoms. Last, in this classification, the term "catatonia" means that the phenotype affects psychomotility, not only consisting in quantitative, but also quantitative psychomotor distortions.

It has a marked bipolar character with hyperkinetic and akinetic episodes, usually with phases of remission. However with the repetition of episodes, residual symptoms, such as apathy, become increasingly noticeable, i.e. it is a relapsing-progressive phenotype. It is the non-systematised schizophrenia with the strongest hereditary component, being of dominant inheritance with incomplete penetrance.

Far from being rare, about 7-10% of the patients hospitalized for endogenous psychosis fulfil this phenotypic diagnosis.

Background

Probably there were few cases of periodic catatonia in the 1954's description of "folie à double forme" (double form madness) by Jules Baillarger or "folie circulaire" (circular madness) of Jean-Pierre Falret. When coining the term "catatonia", Karl Kahlbaum mostly described cases of periodic catatonia. This picture has been mixed with the other forms of catatonia defined by Kraepelin and his successors (systematic catatonia). Kleist described the inhibited end of the phenotype using the term akinetic catatonia but did not differentiated it from motor psychosis. Leonhard achieved to isolate it as an entity thanks to its familial aggregation principle and was the first to demonstrate the significant hereditary component of the condition.

The term "periodic catatonia" was also used by Gjessing to describe a form of motility psychosis with frequent recurrences following a regular pattern. This has no connection to Leonhard’s form either in terms of prognosis, aetiology or treatment (cf. motility psychosis).

Clinical features

The phenotype has a remitting-progressive course.

If psychosis or mood disorder may seem to dominate the clinical picture for a DSM/CIM trained mind, these are nonspecific. The psychomotor disorder is the only constant of this phenotype. If depressive or dysthymic elements frequently appear to precede the first periodic catatonia episode or may even seem constitute the only manifestation, it is just that psychomotor symptoms remained discreet (in a relative of patients).

- Excited or hyperkinetic pole

The excitement has an impulsive character: the patient runs around the room for no reason, bumps into other patients, throws themselves onto the bed, utters inarticulate sounds etc. Movements are parakinetic: they appear clumsy, awkward, bizarre, and the facial expression is grimacing. Excitement commonly produces repetitive behaviour (iteration or stereotypy): the patient knocks on the wall, opens doors, and repeats the same sound over and over in a stereotypic way. One of the characteristic features of periodic catatonia is that symptoms from one pole are mixed with the symptoms of the other pole: while there is a generalised hyperkinesia, the face and the gaze can remain bizarrely fixed.

Mood is more often anxious than cheerful, and is more commonly irritated. Ideas of reference and hallucinations occur inconsistently. The speech may appear poorly organized, maid of more or less simplified and agrammatic fragments of sentences. - Inhibited or akinetic pole

There is poverty of movement. Patients can take on strange postures. If it is a form with "hypotonia", the patient can be moved passively. When there is "hypertonia" the patient presents psychomotor negativism, i.e. a negativism that cannot be explained by delusional thoughts, though inhibition or an excessive emotion. The patient may look reluctant, unwilling to participate, may show a gegenhalten, but the definite sign is the psychomotor ambitendency illustrating that the patient's will is antagonized by its negativism. Negativism can also affect behaviour and become active. Catalepsy can occur in which imposed postures will be maintained, together as a mutism. Hard catatonic symptoms are frequent although generally fugitive. Rituals identical to those seen in manneristic catatonia can also be seen in this phase, but as a general rule they are not at the forefront of the picture.

The characteristic features of periodic catatonia also remain here in that symptoms from one pole are mixed with the symptoms of the other pole: while the body is immobile, a limb may move repeatedly, have iterations or stereotypies, or facial expression may show parakinetic restlessness.

Mood is often somewhat anxious more frequently than depressed, and the patient can present ideas of reference and hallucinations. It is worth noting that the clinical picture of anergic/apathetic depression can be seen in these cases, especially early on. The differential diagnosis with manic depressive illness can then be challenging in the absence of other episode. - Residual symptoms (persistent)

As a rule, after the first episode the residual symptoms are mild. It is the akinetic phases rather than the excited phases that lead more quickly to a deficit. When the deficit is mild, the patients seem to have lost their vitality, lack initiative, their mood seem superficial, their thoughts are somewhat impoverished down and movements become clumsy. Huber’s "pure deficit syndrome", which is accompanied by a marked deterioration in executive function, overlap with this concept, without being fully equivalent (too inclusive). With repeated episodes the deterioration worsens. Patients generaly present more an abulia than an apathy. Incentives frequently drives some motivation but they lake energy to make actions. Their lake of initiative sometime to the point of self-neglect, and alogia can go up to the point that patients no longer respond to questions. There is often an irritability that can give the impression of negativism: the patients can be hostile, rejecting or insulting the people caring for them. The patient may even become violent when approached.

On average after 3 episodes, the abulia is severe enough to make it difficult to keep a job (GAF ~ 50).

In spite of this deteriorated state, a few patients present parakinetic agitation of another part of the body, in particular the face, which takes on a distorted expression (grimacing). In these cases, this parakinesia is different from the tardive dyskinesia induced by antipsychotics since the upper part of the face is also, or indeed primarily, affected and this is never the case with the latter. Finally, some patients can make impulsive decisions, suddenly leaving the examination room or answering without thinking, sometimes talking past the point (Vorbeireden).

As a rule, there is no persistent psychotic symptoms on the long course. Eventually the patient may describe rare and brief psychotic phenomena, possibly distressing, but actively psychotic or mood symptoms never occur out of the episodes.

Finally, some patients may have a compulsive abuse of substances, mostly alcohol and tobacco and/or pseudo ODC symptoms (see schizo-OCD).

The excited/hyperkinetic phases generally last a of several weeks or months. The inhibited/akinetic phases, by contrast, can persist for months or even years. There are often long phases of remission between each episode and it is not exceptional for an individual to present only a single one throughout life. In serious forms, which are fortunately less common, excitement and inhibition can alternate leading residual symptoms to accumulate quickly.

Differential diagnosis

It is sometimes difficult to differentiate periodic catatonia from motility psychosis during an acute episode. Some elements for the differential diagnosis during the episode are:

- A mixed psychomotor distortion, i.e. the presence of excitement and inhibition, that always remain separate in motility psychosis.

- A parakinetic distortion of psychomotricity which never appears in motility psychosis.

- The impulsive character of the excitement in periodic catatonia, which is not seen in motility psychosis.

- Although inconstant, a strict psychomotor negativism, i.e. with ambitendency, points to periodic catatonia.

In case of doubt, the course will more easily allow to distinguish between these two diagnoses. The presence of a relative affected by periodic catatonia should favour this diagnosis.

Phases of perplexed stupor and excited confusion may also be seen, like in confusional psychosis or bipolar disorder, as well as traits of affective paraphrenia and cataphasia. However, differential diagnosis from these disorders is normally straightforward even during the episode. Otherwise, the residual clinical picture should allow to make the diagnosis.

Finally, the differential diagnosis from systematised catatonias is sometimes difficult to make without having enough time course to capture the different evolution of the phenotypes. Periodic catatonia can resemble all of these forms, even for relatively long periods. Only proskinesia is extremely rare and never lasts for long.

The residual clinical picture can be confused with eccentric hebephrenia, according to G. Stöber. Only distortion of psychomolity allows to make the diagnosis.

Parakinesias must be differentiated from tardive dyskinesia and Meige's syndrome (oromandibular dystonia with blepharospasm) based on the pseudo-expressive character, the absence of insight or discomfort, and the lack of repetition, stereotypy or spasticity of movement. They must also be differentiated from physiological movements: restlessness or shoulder relaxation movements.

Proposed criteria (research)

Introductory remarks

There is no doubt that the classical WKL diagnosis is superior to the following operational criteria. Their main purpose is to propose a way to replicate our results by clinicians unfamiliar with the WKL classification.

To preserve group homogeneity, these criteria favor specificity over sensitivity and thus do not cover the full symptomatic spectrum of periodic catatonia. The requirement for a relapsing progressive course is a good example of the limits of these criteria. Such course will not consider the 10% of genuine periodic catatonic patients with purely progressive development. Yet, it is practical for avoiding confusion with system catatonia. In the other way, periodic catatonia without persistent symptoms after ≥ 2 relapses will be discarded to avoid misdiagnosis with motility psychosis. Although this might be rarely observed for trained clinicians, it might be more frequent for investigators unfamiliar with this phenotype. Of note, we warn clinicians not to use the following criteria for epidemiologic or genetic researches.

These criteria remain work in progress. We work hard to make them operative and to validate them, but we cannot guaranty their direct usability by non-WKL trained investigators. Specifically, the detection of parakinesia might require a minimal formation.

The criteria are inspired from those put forward by the Würzburg school, those of Sigmund23,24 and DRC Budapest-Nashville25,26. We urge researchers not to apply the misleading logic of recurrent episode of ICD / DSM catatonia = periodic catatonia. As stated previously, this might be more typical for hyperkinetic-akinetic motility psychosis. Since qualitative distortion of psychomotricity and psychomotor negativism exclude this diagnosis, they should be especially look for. Considering that the latter is not a mere ICD / DSM negativism. We can only advise clinicians and researchers to get trained on videos and supervised in clinical settings.

Finally, as this study was not concerning epidemiology, inheritance or genetics, we also included the family aggregation principle as a minor criterion.

Click on the link opposite to see the current state of the diagnostic criteria in English (wiki page). Only members of the CEP can modify them. However, you are welcome to offer your opinion by sending us an email or leaving a comment (send a mail).

Click on the link opposite to see the current state of the diagnostic criteria in English (wiki page). Only members of the CEP can modify them. However, you are welcome to offer your opinion by sending us an email or leaving a comment (send a mail).

Using the criteria

The background idea is simply to combine typical symptoms, i.e. qualitative disturbance of psychomotricity, with a typical course, i.e. of relapsing-progressive type. Because the former is rarely reported in ICD / DSM oriented case-notes, the criteria require their direct observation by the evaluator. When symptoms are too poorly characteristic, an affected first-degree relative is required.

- Previous episodes are compatible + Observed episode with typical symptoms + Observed remission with typical OR non-typical residuals symptoms.

- Previous episodes are compatible + Observed remission with typical residual symptoms ± Observed episode with non-typical symptoms.

- Previous episodes are compatible + Observed episode with non-typical symptoms + Observed remission with non-typical residual symptoms + affected first-degree relatives.

Compatible episode(s)

For patients with one or many previous episode(s) not observed with the WKL classification in mind, the compatibility of previous episode shall be assured.

Inclusion criteria

The following ICD diagnosis are compatible:

- Affective psychosis (anxiety, depression, mania or any other bipolar episode) no necessary psychotic feature.

- Psychotic episode of any kind except purely delusional.

Exclusion criteria

At least one episode not secondary to:

- Drug use or withdrawal.

- A general medical condition.

- A severe stressor, i.e. no reactive psychosis.

Observed episode

Must be prospectively collected or retrospectively assessed on videotaped interview as it is very unlikely that ICD / DSM oriented case-notes can be helpful. The current episode can fulfill any of the ICD diagnosis criteria mentioned in the “compatible episode” section.

Criteria for the akinetic pole

Both criteria must be present (logical AND):

- Akinesia OR stiff, empty facial expression OR stupor.

- Strange postures OR mutism OR depressive or anxious mood.

Criteria for the hyperkinetic pole

Both criteria must be present (logical AND):

- Hyperkinesia OR psychomotor restlessness non-influenced by external stimulation.

- Elated mood OR impulsive actions or talking OR purposeless aggression

Exclusion criteria

Not secondary to:

- Drug use or withdrawal.

- A general medical condition.

- A severe stressor, i.e. no reactive psychosis.

Observed episode with typical symptoms

Must fulfill the diagnosis for “observed episode” + the intermittent presence of one of these symptoms. It may last only an hour in an episode of several months:

- Mixed motility disorder: some segments or limbs or face are akinetic while others are hyperkinetic.

- True psychomotor negativism, i.e. with evoked ambitendency.

- Parakinesia.

- Distorted facial expression (inappropriate gesture/expression).

- Waxy flexibility OR true catalepsy, i.e. not simple "Haltungsverharren".

Observed episode with non-typical symptoms

Must fulfill the diagnosis for “observed episode” + the intermittent presence of one of these symptoms:

- Fixed gaze.

- Motor or speech perseverations.

- Stereotypies or iterations neither caused by affective tension nore by thought inhibition, i.e. not a mere release phenomenon.

Observed residual state

Although full or nearly full recovery can be observed after a first episode, residual symptoms should be present in case of > 2 relapses either typical or non-typical.

Exclusion criteria

- Illogicality or blurring of concepts OR syntactic or semantic disorder of language persisting between episodes.

- Systematized chronic paranoiac delusion with designated persecutor OR a delusion purely connected to affect/passion, i.e. erotomania, jealousy, persisting out of the episodes.

- Features of system catatonia: echolalia, echopraxia, proskinesia (forced grasping, non-resistance to pressure or limb positioning).

Observed residual state with typical symptoms

Must fulfill the diagnosis for “observed residual state” + the intermittent presence of one of these symptoms at least at a mild degree:

- Staring.

- Parakinesia.

- Grimacing.

- Slight psychomotor negativism.

Residual state with non-typical symptoms and an affected first-degree relative

Must fulfill the diagnosis for “observed residual state” + one of these symptoms:

- Abulia OR apathy not caused by depression or too high D2 blockade.

- Reduction of expressive movements, mild akinesia up to a robotic aspect not part of antipsychotic extrapyramidal syndrome, i.e. rigidity to passive movement absent or clearly insufficient.

- Emergence, i.e. not previously existing, of stiffness, clumsiness or distortion of movements.

- Incomplete insight.

+ An affected first-degree relative.

Relationship with the international classifications

The international nomenclature systems have defined catatonia based on list of symptoms admitting a large number of combinations (see DSM5's criteria). It follows that the criteria are actually mostly filled by cycloid psychoses (primarily motility psychosis). Cases of periodic catatonia only occasionally meet the ICD or DSM criteria for catatonia, even when using the more flexible DSM5 criteria. Indeed Leonhard used the term catatonia in the same meaning as Kahlbaum and Kraepelin: a disorder of the psychomotor functions, i.e. involving will and its motor implementation, execution and monitoring. In addition to his predecessor’s definition, Leonhard stated that the disorder must be qualitative rather than simply quantitative. A pure quantitative disorder is observed in motility psychosis.

In multiple-diagnosis studies, periodic catatonia cases are split between the DSM-III-R diagnoses of bipolar disorder (20%), schizoaffective disorder (30%) and schizophrenia (50%). The diagnosis depends chiefly when patients are observed. It is worth noting that early on in the course, 50% would fit the French definition of "bouffée délirante aiguë" (equated with acute psychotic disorders).

However the spectrum of symptoms that these patients may present is vast and may fulfil many diagnoses:

- Unipolar or bipolar disorder.

- Anxiety disorder, especially social phobia, which is in fact a form of negativism.

- Personality disorder, especially impulsive type.

- Obsessive-compulsive disorder (pseudo-OCD or schizo-OCD).

- Addictive disorder: alcohol abuse or heavy cigarette smoking can be observe in the patients themselves, but their relatives are often also subject to addiction with occupational impairment.

Predisposing factors

The mean age of onset is 24 years, but there is very significant variation with forms in both children (the earliest onset was 7 years of age) and the elderly. It affects both sexes in equal measure.

This is a strongly hereditary disorder with 22% of first-degree relatives affected, equating to a cumulative risk of morbidity of 26% (taking the effect of age into account). If relatives who present a distortion of their psychomotility are taken into account, the proportion of affected first-degree relatives is 36%. Heredity appears to be dominant with incomplete penetrance. Chromosomes 15q and 22q had been predicted to be involved since the earliest association studies. However the study of numerous genes in 15q turned out to be negative. Using the SNP method four very strongly associated loci have been demonstrated, and these are currently being explored.

By contrast, any effect for birth season, infection during pregnancy, or perinatal problems compared to a normal population has been discounted.

Prognosis

Periodic catatonia progresses to a pronounced decline only in rare cases. Most of the time the major residual symptom consists of weakness and apathy. The prognosis for periodic catatonia is therefore fairly good as long as episodes do not build up (GAF = 60 ± 20). Arstrup has reported the regression of residual symptoms over time once new phases of exacerbation have stopped occurring (but this will take over 10 years).

Treatment

Acute phase

Antipsychotics are often essential whatever the acute manifestations: agitation, anxiety, psychosis, exaltation as well as inhibition/akinesia. This phenotype might be relatively resistant among non systematized schizophrenias, since only 60% improved under classical antipsychotics. Clinical observations suggest that it is in such forms that CLZ outperform the other antipsychotics. Good results have also been reported with OLZ. The OLZ/QTP/CLZ or aripiprazole should be preferred when the akinetic pole predominates. This recommendation is not based on the risk of malignant syndrome which does not seem to be significant in this condition as it is in motor psychosis. These medication are also superior in the long-term, as patients appear frequently "robotized" after several weeks under first generation or RISPERIDONE / PALLIPERIDONE. This effect appears not to be assimilated to a classical extrapyramidal effects as it might not be associated with rigidity on examination and is not very sensitive to anticholinergics.

An add-on of a mood stabilizer to the antipsychotic often allow further improvement even if the symptoms are not those of ICD / DSM's bipolar or schizoaffective disorder. It is customary to favor LMT in akinetic forms and lithium in hyperkinetic forms. In the absence of specific studies, other antiepileptic mood stabilizers as supposed to work as well.

Benzodiazepines are specially interesting as add-on treatment of agitation, anxiety and especially of inhibited catatonia. However in the latter the therapeutic response is usually partial and generally vanish after weeks or months.

Finally ECT remains the treatment of choice in resistant forms whatever the clinical picture, e.g. catatonic, mood, anxiety, psychotic, pseudo-OCD disorder ... One must however accept to perform up to 15 sessions before observing a response. Except in case of a first episode, full remission is rare.

Stabilization phase

Once past the acute phase, the consolidation phase is the opportunity to optimize the therapeutic to reduce other disabling symptoms.

The treatment of the deficit syndrome can be considered already at this stage. It generally relies on antidepressants with noradrenergic effect (doxepin, SNRI, tricyclic ...). Non-selective, irreversible MAO inhibitors are very effective on apathy but should be used with caution and only under an effective mood stabilizer. Indeed, whereas they are poorly at risk to induce a switch or mixed state in MDP, they are at high risk of triggering a hyperkinetic phase in periodic catatonia. The MODAFINIL is valuable when apathy takes the form of an hypersomnia (sometimes induced by CLZ). However this effect should be appraised against the possible increase of impulsivity and parakinesia. The risk to increase psychosis has been described in schizophrenia and thus the triggering of an hyperkinetic phase cannot be ruled out. However, we still haven't observed such event in clinical practice. METHYLPHENIDATE has been used in few patients, on whom it increased impulsivity. Although there is no specific study in periodic catatonia, high frequency rTMS of the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex has a definite although modest positive effect on negative symptoms (average improvement 3pt PANSS-negative / 6pt the SAPS). As rTMS has very few side effects, the risk / benefit ratio is excellent. Finally, in advanced deficit states, occupational therapy and patient stimulation in day clinic are at needed.

Persistent anxiety can be difficult to manage. The BDZ help but are rarely sufficient in the medium term. PREGABALINE is successful, but generally also tends to lose its effectiveness with the need to increase the doses. SSRI / SNRIs are poorly effective. The add-on of a mood stabilizer may help. It is often helpfull to use low potency antipsychotics such as CYAMEMAZINE, with their frequent sedative side effects. So far, attempts to use BACLOFEN motivated by its results in some anxiety and the richness of GABA-B receptor in the portion of the cingulate cortex affected by the pathology was disappointing.

Pseudo-OCD symptoms are partially responsive to high doses of SSRI + LMT. The improvement is however limited (see dedicated page). Electroconvulsive therapy should be considered in case of high resistance. The role of rTMS in this case remains to be determined.

Maintenance treatment (stable phase)

Maintaining long-term antipsychotic remains the rule primarily in case of impulsivity or residual anxiety. But in order not to make apathy worse, it is recommended to reduce the dose particularly when there is no aripiprazole or OLZ/QTP/CLZ. Although probably protective against recurrence, antipsychotics might essentially hide small relapses.

At the opposite lithium might be truly protective. In a retrospective study on ICD/DSM bipolar disorder of unfavorable evolution, 5 patients on 7 suffered from periodic catatonias. All had the same story of lithium initiation early in the course of the disease, a rather benign course while the lithium was maintained, and a rapid aggravation on discontinuation, almost as if patients were “catching up”. Sometimes patients had a pseudo-dementia syndrome ("démence vésanique"). The reintroduction of lithium never allowed a return to the initial state. The Würzburg's team has not seen any clear superiority of lithium in comparison with other mood stabilizers. But it could be that the effect take some time to emerge. We hypothesized that the protective effect of lithium against dementia in ICD / DSM's bipolar disorders might be especially true for the pseudo-dementia of periodic catatonia. Importantly such protective effect has been reported to be specific to lithium in contradistinction with antiepileptic mood stabilizers. The introduction of lithium helps to reduce the dosage of antipsychotics in order to improve the drive and the initiative.

The treatment of the deficit syndrome has already been described.

Etiopathogenic hypothesis

According to Leonhard periodic catatonia is said to be a non-systematised form of schizophrenia. In his mind this meant that multiple "neurological systems" would be involved in contradistinction to the systematized forms in which only one such system was supposed to be involved. This assumption primarily relied on the polymorphic feature of the former and the monomorphic, invariable aspect of the latter. While he supposed that periodic catatonia might not correspond to the degeneration of one system, Leonhard’s hypothesized that a regulatory system could be affected.

Aetiology

In terms of aetiology, the disease is undeniably inheritable. However, there still have been no descriptions of specific genes involved in the pathology. Chromosome 15q15 has been reported to be implicated in two cases series (MIM 605419). But it has been widely explored by positional cloning and systematic mutation screening with no results. However there is no large pedigree and the disease is very likely to involve multiple genes, since in a pooling-based genomewide SNP association study, four loci were put forward (7p14.1 and 19p12 were the most replicated candidates). In contrast to all expectations, CNV are more numerous in juvenile periodic catatonia (< 15Y) although this is not significantly different to systematised catatonias. By contrast, the numbers of CNV are significantly greater than in the cycloid psychoses. However, this is only a CNV load, and no chromosome region seems to be more particularly affected.

Pathophysiology

Considering the characteristic symptoms of the disease, a tentative hypothesis would have been the involvement of a regulatory loop passing through the basal ganglia.

Considering the characteristic symptoms of the disease, a tentative hypothesis would have been the involvement of a regulatory loop passing through the basal ganglia.

But in an ongoing study that was yet the cingulate cortex that seemed affected (Connect C3 - NCT02868879). Even if this structure was the only one to be affected, its involvement could elegantly explain all the symptoms: psychosis, mood disorder, akinesia, hyperkinesia, catatonia (akinetic mutism) and parakinesia... Indeed, the distortion of facial expressions, preferentially involving the upper part of the face is very consistent with the participation of the cingulate motor area (CMA). The mixed motility disorder characteristic of the acute phase was initially interpreted as a breach of the basal ganglia's regulatory loops. But this should be reinterpreted in the light of this demonstration of an isolated cortical involvement.

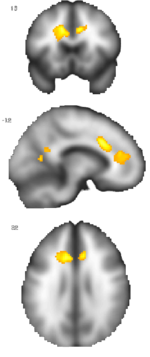

An increase of paramagnetic iron in the cingulate cortex which correlate with residual symptoms and the number of episode rather than the duration of the disease (see image) was suggestive of a microglial activation. This could be a possible explanation for the specific loss in subpopulation of GABAergic interneurons reported in 30% of autopsied schizophrenia although it remained to be demonstrated that these correspond to periodic catatonia cases. Still the current hypothesis is that periodic catatonia could be a limited autoimmune encephalitis affecting specific cell population of the cingulate gyrus. There might be a predisposition due to specific HLA haplotype and a later opening of the blood-brain barrier and/or an immune activation. This inflammatory thesis is under investigation.

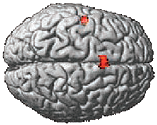

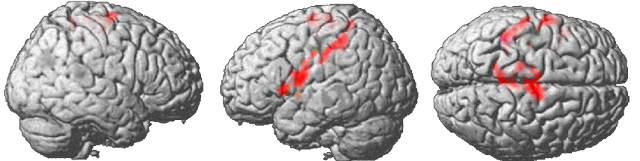

A disordered inhibition of the motor and premotor cortices further strengthened by the analysis of the functional activity carried out in the same study (Connect C3 - NCT02868879). Patients suffering from periodic catatonia were compared not only to controls, but also to other patients suffering from another psychosis (cataphasia) and thus also treated with antipsychotics. Rather than a reduction in the activity of these cortices, an increase has been observed (in red, figure below). A study carried out at the University of Bern that probably included a majority of patients suffering from periodic catatonia found a very similar result (adjacent figure).

A disordered inhibition of the motor and premotor cortices further strengthened by the analysis of the functional activity carried out in the same study (Connect C3 - NCT02868879). Patients suffering from periodic catatonia were compared not only to controls, but also to other patients suffering from another psychosis (cataphasia) and thus also treated with antipsychotics. Rather than a reduction in the activity of these cortices, an increase has been observed (in red, figure below). A study carried out at the University of Bern that probably included a majority of patients suffering from periodic catatonia found a very similar result (adjacent figure).

References

Below are the reference texts and additional material for periodic catatonia:

- Extract from "Classification of endogeneous psychosis", ed. 1999. p. 104-112 (see English version). Translated from "Aufteilung der endogenen Psychosen", ed. 2004. p. 109-118 (see German version). The French translation is underway "Classification des psychoses endogènes" (see French version). It has been tranlated in Spanish as well "Clasificación de las psicosis endógenas", ed. 1999. (see Spanish version) (see books).

- Extract from "Diagnostic différentiel des psychoses endogènes" (differential diagnosis of endogenous psychoses), ed. 2014. p. 40-42. Traduit de "Differenzierte Diagnostik der endogenen Psychosen", ed. 1991. p. 30-31 (cf. version allemande) (see books).

- Extract from "35 psychoses", ed. 2009. p. 139-148 (see books).

- WKL Strasbourg Symposium in 20-11-15 "Periodic catatonia and the different forms of systematic catatonia"

Research articles

- Foucher JR, Zhang YF, Roser MM, Lamy J, De Sousa PL, Weibel S, Vidailhet P, Mainberger O, Berna F. (2018) A Double Dissociation Between Two Psychotic Phenotypes: Periodic Catatonia and Cataphasia. Progress in Neuropsychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry (article, supplement1, supplement2) (doi) (Video presentation).

- Foucher JR, Jeanjean LC, de Billy CC, Pfuhlmann B, Clauss JME, Obrecht A, Mainberger O, Vernet R, Arcay H, Schorr B, Weibel S, Walther S, van Harten PN, Waddington JL, Cuesta MJ, Peralta V, Dupin L, Sambataro F, Morrens M, Kubera KM, Pieters LE, Stegmayer K, Strik W, Wolf RC, Jabs BE, Ams M, Garcia C, Hanke M, Elowe J, Bartsch A, Berna F, Hirjak D. The polysemous concepts of psychomotricity and catatonia A European multi-consensus perspective. European Neuropsychopharmacology. 2022; 56(3):60-73. (supplément).

- Pfuhlmann B, Berna F, de Billy C, Arcay H, Gawlik M, Roth J, et al. Edward Shorter’s comment on Jack R. Foucher et al. Wernicke-Kleist-Leonhard phenotypes of endogenous psychoses: a review of their validity. INHN. 2020. p. 1–13.

- Roser MM "Etude de la catatonie périodique en IRM multiparamétrique" (Investigation of periodic catatonia using multiparametric MRI) Master thesis, 25-05-2016.

- Stöber G, Saar K, Rüschendorf F, Meyer J, Nürnberg G, Jatzke S, Jatzke S, Franzek E, Reis A, Lesch KP, Wienker TF, Beckmann H. Splitting schizophrenia: periodic catatonia-susceptibility locus on chromosome 15q15. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;67(5):1201–7.

- Walther S, Schäppi L, Federspiel A, Bohlhalter S, Wiest R, Strik W, Stegmayer K. Resting-State Hyperperfusion of the Supplementary Motor Area in Catatonia. Schizophr Bull. 2017;43(5):972–81.